First Conference – 1920, UK

First CFC – Great Britain, 1920

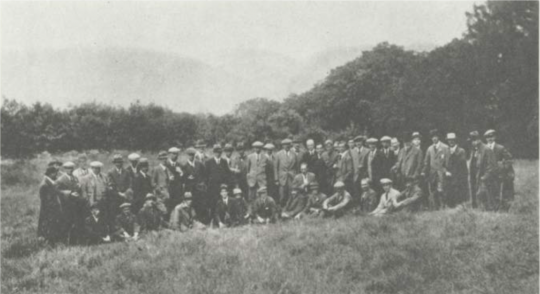

STANDING: A. Henry, A.D.Hopkinson (For.Comm.), L.Palfreman (Sierra Leone), H.R. Mackay (Victoria), H.M. Thompson (Nigeria), D.J. Davies (Newfoundland), V.F. Leese (For.Comm.), Wm. Dawson (Cambridge), Sir Claude Hill (India), W.F. Perree (India), R.L.Robinson (For.Comm.), E.Battiscombe (East Africa), Sir James Connolly (West Australia), A.J. Gibson (India), A.N. Glover, J.D.Sargent (Ceylon), the Lord Clinton Crozier (For. Comm.), W.H.Kilby (Canada), R.F.C. Osmaston, N.C. McLeod (Gold Coast), J.M.Purves (Nyasaland), Lord Bleddisloe, Col.B.W.Petre, R.R.Grundy (Melbourne), H.J.Elwes, Robson Black (Canada), M.C.Duchesne, P.Groom, Sir Peter McBride (Victoria), E.H.Finlayson (Canada).

SITTING: C.S.Rogers (Trinidad), B.W.Adkin, D.K.S. Grant (Tanganyika), C.E.Legat (S.Africa), Hon.F.D.Acland (For.Comm.), L.S.Osmaston (For.Comm.), Hugh Murray (For.Comm.), C.E.Cubitt (F.M.S.), M.A.Grainger (British Columbia), P.H.Clutterbuck (India), R.S.Troup (India and Oxford), C.O.Hanson (For.Comm.), O.J.Sangar (Secy.), R.Fyffe (Uganda).

H.L. Edlin, Commonwealth Forestry Conferences: 1920 to 1962

The first Commonwealth Forestry Conference met in London from 7th to 22nd July, 1920, and the proceedings opened with the presentation of a loyal address to King George V. The conference chairman was Major-General Lord Lovat, K.T. , K.C.M.G., D.S.O. a distinguished soldier who had pioneered forestry developments on his vast estates in the north of Scotland, and had recently been appointed the first chairman of the newly-formed Forestry Commission of Great Britain.

The First World War had only just come to an end, with the politicians redrawing the maps at their conference tables. There had been little effective interchange of forestry ideas between Commonwealth countries since 1914, for every service had been pre-occupied with the task of securing adequate timber supplies for the fighting forces. In fact, the war had nearly been lost on the industrial front because the German submarine campaign had cut down the import or timber, and particularly pit props for the vital coal mines, to the British Isles. This conference met, therefore, against a background of depleted limber reserves, and a keen awareness of the need to conserve and develop those forest resources that had long been considered inexhaustible. It was a unique occasion, for never before had the forestry leaders from lands with the greatest forests in the world, such as India and Canada, met to consider their-common problems and to work out the advantages that could accrue to all through cooperation.

Considering the novelty of the meeting, and the difficulties facing forest services still struggling with post-war reorganisation, the geographical representation was remarkably wide. Australia, Canada , India and New Zealand were all there, and the Colonial Office sent senior local officers from ten colonies scattered over three continents. Altogether, thirty countries or provincial services found a seat at the conference table.

Five of the countries who sent representatives have since elected to leave the Commonwealth, and to pursue independent political destinies. These are the Republic of Ireland, the Union of South Africa, Burma, Egypt and the Sudan. But in recording this it becomes imperative to add that the co-operation which this conference, and several of its successors, built up between all concerned, has continued as a vital force to the present day.

The main resolutions passed by this first conference covered forest policy, the survey of forest resources, the organisation of forest industries, publicity, research and education. Provision was wisely made for future conferences, with a Standing Committee to co-ordinate activities during the intervals between each. Plans were laid for the interchange of valuable strains of forest trees between the participating countries, and for a common scheme of forest terminology and trade names for Commonwealth timbers. Thought was also given to the establishment of a “Forestry Bureau” for the review of the world literature and the interchange of scientific information, an idea that has since borne most effective fruit in the Commonwealth Forestry Bureau at Oxford University, and the regular publication of that indispensable quarterly Forestry Abstracts.

The tours that followed the conference began with visits to Windsor Castle and the extensive and well-managed woodlands owned by the Crown within the old Royal Forest of Windsor. Visits were paid to an Empire Timber Exhibition in London and to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in Surrey. The Kew Herbarium and Library have of course been the fountain-head of the botanical knowledge that has enabled foresters throughout the Commonwealth to identify their tree, and exploit their timbers to full advantage.

At this early date the Forestry Commission of Great Britain had only just planted its first tree! So, instead of looking at new forests, the delegates visited the Royal Forest of Dean which has been a national property since the days of William the Conqueror (A.O. 1066) if not before. Here they saw occasional oaks surviving from plantations made by Charles II and visited the Speech House, still a court of forest law, that he built in 1680. They reviewed large areas of maturing oaks planted, on the advice of Admiral Lord Nelson, during the Napoleonic wars (1795-1815) to provide ship timbers for a future Royal Navy. They saw too the conversion of old woodlands to modern needs, following plans drawn up by Professor Sir William Schlich, the great German pioneer of modern scientific forestry, who had previously been Inspector-General of Forests for India. The party then travelled north to Scotland, to visit four leading private estates in the Highlands. Besides Lord Lovat’s own woodlands around Beaufort Castle, near Inverness, they saw the Novar estates in Ross-shire. Here Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson had established sample plots of exotic conifers that were already providing vital information to guide the choice of tree species for Britain’s future forests – plots that served as a model for many similar series of comparative trials throughout the Commonwealth. On Speyside they saw the Earl of Seafield’s woodlands – which are still the most extensive privately owned forest in Britain – and admired, around Castle Grant in Morayshire, magnificient natural stands of the native Scots pine, surviving from the ancient Forest of Caledonia. By contrast, they also saw the Murthly Estate in Perthshire, owned by Colonel Steuart-Fotheringham, where pioneer introductions had been made of new trees from North America. Among these, the Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) and the Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophyla) were destined to assume major importance as Scotland’s afforestation programme developed.

Excerpt from:

Commonwealth Forestry Conferences: 1920 to 1962

H.L. Edlin

The Commonwealth Forestry Review

Vol 46, No 3 (129) (September, 1967), pp 192-200 (10 pages) Published by the Commonwealth Forestry Association